I think most people who use X-Plane go through an evolution where they launch flights directly from the runway with engines running, then they’ll want to try starting their plane up from cold and dark, and eventually, they want to fly procedures and do things by the book.

Gauges. So many gauges.

When I signed up for the online ATC network, PilotEdge, I became aware I’d need to at least somewhat learn how to do things by the book. It was a bit intimidating. Even a basic thing like how to fly a traffic pattern is confusing if you’ve never done it before, let alone what to say to ATC when departing a towered airport.

So, after a few months, I’m still a rookie on PilotEdge, but I thought I’d write a post summarizing a few things I figured out along the way. This is intended for people like me who didn’t have previous aviation knowledge or experience with online ATC like VATSIM.

MOSTLY UNNECESSARY DISCLAIMER: I’m just a guy playing a video game. Don’t take any of this as real-world aviation advice. It’d be like taking medical advice from someone who’s played a lot of Surgeon Simulator.

Basics:

For PilotEdge, you need a headset with a mic (don’t be the guy using his laptop’s built-in mic who sounds like he’s underwater while watching Grey’s Anatomy).

When you connect to the network, your aircraft needs to be parked on a ramp.

Your callsign (configured in the PilotEdge settings) must follow FAA guidelines

Most people use real weather, but it’s not a requirement.

You only have to talk to ATC if you’re flying somewhere where you have to talk to ATC.

Tips:

PilotEdge has a rating program for both VFR and IFR pilots. It’s a good way to learn the ropes.

PilotEdge also has free video workshops covering the basics.

Things to know before starting (if you want to fly VFR):

You should know how to read a VFR map, fly a traffic pattern, and make CTAF calls.

Reading a VFR Map:

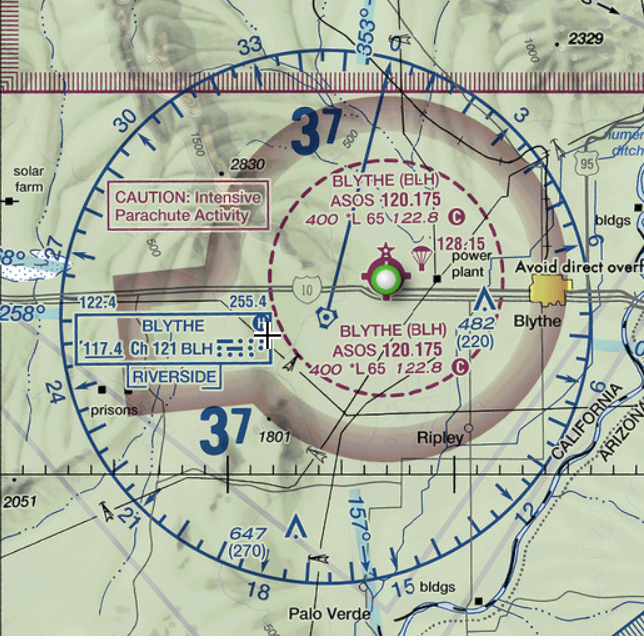

Go to Skyvector to view VFR maps. Airspaces are color-coded with magenta or blue lines.

Class B Airspace: Thick solid blue lines. To enter this airspace, you need to be talking to ATC and hear the magic words, “Cleared to enter the Bravo airspace”

Class C Airspace: Thick solid magenta lines. To enter this airspace, you need to be talking to ATC and they need to use your callsign in their response.

Class D Airspace: Thin dashed blue lines: To enter this airspace, you need to be talking to ATC and they have to use your callsign in their response

Class E Airspace: Most of the time, Class E airspace exists between 1200 feet AGL and 18,000 feet MSL. Sometimes it starts lower, in which cases it’s marked on the map as either a thin dashed magenta line (indicating starting at surface), or magenta gradients (indicating starting at 700 feet AGL). Class E is controlled airspace (that exists for IFR flight), and you do not have to talk to ATC when flying VFR. When it does start lower than 1200 feet AGL, it is to protect for an instrument approach at a nearby field.

TRSA (Terminal Radar Services Area) - Thick solid gray lines. Optional radar services are provided in this area. Pilots are encouraged, but not required, to use these services.

Restriced: Hashed blue lines, usually around military areas. You need permission to enter.

MOA (military operations area): Hashed magenta lines. You are not required to talk to ATC to enter, but it’s generally a good idea to do so, especially if the MOA is active. Each MOA has a name, such as “Abel North MOA”, and you can find its schedule printed in the margins of the VFR chart.

Towered airport - blue solid circle or blue solid runway lines. Lines show number of runways and approximate orientation. The star indicates it has a beacon, the squares sticking out indicate fuel services available.

Non-towered airport - magenta solid circle. The number next to the C that looks like the copyright symbol is the CTAF frequency. In this case, it’s 122.8. Beneath it, “RP 26” indicates Runway 26 uses Right Pattern traffic. “*L” means it is lighted, but the asterisk indicates with limitations (for example, the pilot may need to activate the lights with his radio). The 2222 is the field elevation. The bolded 134.625 is the weather frequency. The red flag indicates this spot is a VFR visual reporting point that can be used to tell ATC where you are located.

Not depicted on sectionals:

Class A Airspace: IFR only, extending from 18,000 feet MSL to 60,000 feet MSL. The realm of jetliners.

Class G Airspace: The only uncontrolled airspace, usually between the surface and wherever Class E starts (usually 1200 feet AGL). No ATC or radar services in Class G. In some remote parts of the US where there is no ATC, Class G may be specifically called out on the sectional as a blue gradient, in which case it extends from the surface up to 14,500 feet MSL. You’re on your own in Class G.

Airspaces are divided into shelves which begin and end at different altitudes. Inside each shelf, you will find two numbers which look like a fraction printed in the same color as the airspace lines. The top number is the top of airspace, in hundreds of feet, and the bottom number is the bottom of the airspace:

“40/SFC” means the inner ring extends from the surface to 4000 feet. “40/15” means the outer ring extends from 1500 feet to 4000 feet. If you fly above or below these numbers, you are not in the airspace. So, if you flew over Santa Barbara at 6000 feet, you would not need talk to ATC because you are not within Santa Barbara’s airspace.

Smaller airports may only have one shelf. Instead of a fraction, the shelf height is written as a number in a dashed square. The “28” in the dashed square means the airspace extends from surface to 2800 feet.

FLY A TRAFFIC PATTERN

This one was a bit of a mystery to me initially, but it’s straightforward:

The pattern is like a traffic circle, except it’s a rectangle. Planes enter and exit at a set location. It defaults to 1000 feet above ground or the traffic pattern altitude listed on the airport’s chart. The four legs of the rectangle are:

Downwind - runs parallel to the runway 1/2 mile away, flying with the wind. For low-wing aircraft, a rule of thumb is that the tip of the wing should visually just touch the runway when you look out the plane’s window. For high-wing aircraft, the runway should visually appear half-way up the wing strut. Typically you begin to descent in the downwind once you are abeam your touchdown point.

Base - when flying the downwind, you should turn 90 degrees onto the base leg when the runway is over your shoulder along a 45-degree line. You continue the descent started in the downwind all throughout the base leg.

Final or Upwind - you should always land flying into the wind (upwind, or with a headwind). This is because with a tailwind your plane will have to travel faster (relative to the ground) to generate the same lift compared to flying into a headwind. In other words, you’ll have to land at a higher ground speed and take more runway to stop. If you are flying on the runway’s extended centerline you are on Final. If you are flying parallel and offset to the runway (usually intending to go around the runway and not land) you are on the Upwind. When you turn base to final, typically you are 500 feet above the ground.

Crosswind - when you are between 500 - 700 feet above ground, you can turn 90 degrees onto the crosswind leg. You would then continue climbing to pattern altitude. When the runway is along a line 45 degrees behind you, you turn onto the Downwind.

The pattern is either clockwise (right traffic) or counterclockwise (left traffic). For left traffic, you make all left turns; for right, all right turns. This is usually published on the airport chart. Many airports also have a segmented circle on the ground which shows the pattern direction, usually with a windsock in its center.

For non-towered airports, planes should enter the pattern level on the downwind along a 45 degree angle. This gives them the best visibility to see planes already in the pattern; however, in reality planes may enter any leg of the pattern, including the upwind, if it makes more sense due to direction of travel or terrain.

For non-towered airports, it is recommended planes depart straight out or on a 45 degree, but in reality planes may depart any leg of the pattern based upon what makes sense for direction of travel.

Arriving/Departing Non-Towered Airports

The runway number is roughly the heading of the runway, minus the zero. Runway 18 is along magnetic heading 180.

When you get the weather for an airport, it will give you the direction the wind is coming from. Ideally, you’d like to landing flying into the wind, so you try to match the wind direction to the closet runway heading. If the wind is coming from heading 240, then you’d like to land on runway 24, or the nearest number to 24. The same rule is true for choosing a runway for take off. If there’s no wind, refer to the airport plate to see if there is a preferred runway, or see which runway everyone else is using.

When arriving, generally you’ll descend to pattern altitude, enter the downwind on a 45 degree, turn base, turn final, and land.

When departing, generally you’ll fly straight out and climb to 500 feet above pattern altitude, then turn to your desired heading and continue climbing to cruise altitude.

Arriving/Departing Towered Airports

You must talk with ATC prior to entering the airspace of a towered airport. More on that later.

If flying to a towered airport, ATC will give you instructions based on what makes sense for the direction you’re arriving. They may have you fly straight in or enter any segment of the pattern. Don’t automatically enter the downwind on a 45 degree. For towered airports, you enter the pattern where they tell you.

When leaving a towered airport, you’ll follow ATC instructions. Similar to arrival, ATC may have you depart from a specific leg of the pattern or along a specific heading.

If they give you no instructions, then you’ll probably depart the same way you would from a non-towered airport. In that case, you have no restrictions and are free to fly per the normal VFR rules.

NEXT: Making CTAF Calls

When approaching a non-towered airport, you self-broadcast your intentions on a common frequency, called CTAF, which you get from the VFR sectional or airport chart.

It’s kind of like using a blinker in a car. Imagine if, instead of using your blinker, you rolled down your car window and yelled, “LA traffic, Nissan Rogue, turning left!”. That’s pretty much what a CTAF call is.

The format is easy: “(airport name) traffic, (callsign), (what I’m going to do), (airport name)”

An example is “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, entering left downwind runway eight, Banning.”

The calls you’ll probably make are:

Taxiing to the runway: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, taxi runway eight, Banning.”

Taking off: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, departing runway eight, straight out departure, climbing three thousand five hundred, Banning.”

10 Miles from Destination “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, ten miles south at three thousand five hundred, entering left downwind, runway eight, full stop, Banning.”

Entering the Downwind: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, entering left downwind, runway eight, full stop, Banning.”

Turning Base: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, turning base, runway eight, full stop, Banning.”

Turning Final: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, final, runway eight, full stop, Banning.”

Clear of Runway after Landing: “Banning traffic, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, clear, runway eight, Banning.”

CTAF calls are only for CTAF frequencies. Do not make CTAF calls when on ATC frequencies.

NEXT: Talking with ATC to Depart a Towered Airport:

First, it helps to understand the sequence of frequencies at a towered airport. In order:

Clearance Delivery: Used for IFR clearance and VFR departure at some larger airports. The airport’s ATIS will give you directions if VFR departures need to contact clearance delivery.

Depending on what you’re doing, you may get restrictions, a departure frequency, and squawk code. They will be in this format:

On departure fly heading…

Maintain VFR at or below…

Departure frequency…

Squawk…

You will need to read back all of that, so have it written down.

Ground: If you want to use a taxiway or runway, you need permission from Ground.

Before you contact Ground, get the weather by tuning to the airport’s ATIS or AWOS. It’s updated hourly and there’s a phonetic letter code that identifies it. Write down the code.

For a basic VFR departure: “(airport) Ground, (callsign), (location in the airport), (departure direction), taxi with (weather code information)”

Example: “John Wayne Ground, November Three Five Niner Golf Charlie, east ramp, west departure, taxi with kilo.”

The ground controller will respond with a runway and directions to get there: “Runway 20 Left at kilo, taxi via alpha, hotel, charlie.”

You then repeat back the instructions.

Depending on what you’re doing, you may get restrictions/departure frequency/squawk code at this point (if Ground is the first person you’re talking to)

Tower: When you taxi, it will usually be to the hold short lines for a specific runway. At that point, you switch to Tower frequency. You can switch on your own without Ground telling you to. “Tower, November three five niner golf charlie, holding short, runway 20 left at kilo.”

At this point, tower will likely clear you for takeoff. “Runway 20 left at kilo, cleared for takeoff.” You may also get departure directions, such as “Left downwind departure approved”, which means you would take off, turn crosswind, turn downwind, and continue on the downwind heading climbing to cruise altitude (or the altitude restriction you were given)

DO NOT SWITCH OFF THE TOWER FREQUENCY UNTIL INSTRUCTED BY TOWER TO DO SO.

If you will continue to have radar services once you leave tower’s airspace (if you have requested flight following), or for larger airports which have Departure manage their outer airspace rings, tower will tell you to change frequencies to Departure. You’d respond with “Over to departure” and change frequencies.

If you will not have radar services after leaving tower’s airspace, you probably won’t hear from Tower again. Once clear of their airspace, you can change frequencies on your own.

Talking with ATC to Land at a Towered Airport

For a small Class D airport, this is simple:

Get the airport weather before making the call

Contact Tower before entering the airspace: “San Luis Tower, November Three Fine Niner Golf Charlie, twelve miles east, full stop landing with kilo.”

Tower will then issue instructions, usually giving you a report location (“report three-mile final”). When you report, you will be given a landing clearance.

For larger airports that have inner and outer rings to their airspace, you would typically call Approach first. Approach manages the outer ring and the surrounding area, while Tower manages the inner ring. You can get Approach frequencies from the airport’s diagram.

COMMON MISTAKES ON PILOTEDGE

You’ll find the controllers on PE are helpful and give you tips when you make mistakes. There are a few common mistakes that you’ll hear over comms:

Switching from Tower to Departure on your own (You must stay on frequency until told to switch)

Not realizing you need permission to taxi at a towered airport. (Contact Ground for permission to taxi)

Having a callsign with O or I, which is not a valid FAA callsign.

Confusing right/left instructions, such as entering a right base when told to enter a left base.

Not knowing where you’re at in the airport or being vague when calling Ground. Some large airports may have multiple transient parking locations and seprate east/west ramps, so just saying transient parking may not be enough.

Not having the weather before contacting ATC.

Not giving another pilot a chance to read back ATC instructions before you broadcast your request.

PILOTEDGE QUIRKS:

Usually, there are only one or two controllers covering all of the areas. So, even though you change frequencies, it will be the same person.

If you are tuned to any frequency where you can hear a controller, you’ll hear everything they say on all frequencies. This is to help you avoid stepping on transmissions you can’t hear. So, if you hear them give a long clearance, you should know that someone has to read all of that back and you should wait before speaking.

At peak times, the number of online pilots is in the twenties. You probably will not encounter another player unless you are at a popular large airport, like KSNA John Wayne. PilotEdge also publishes focus fields each week, which encourages pilots to congregate at a specific field.

PilotEdge has drones, which are NPC AI aircraft flying routes a bit like World Traffic. Like World Traffic, they are oblivious to your presence, and will land on top of you. Their many purpose is to give you and ATC targets to look out for, when looking for traffic.

Phew! Okay, that was a lot of info. And that’s just VFR flying. I didn’t touch on VFR with flight following or IFR. Hope this helps, and see you on PilotEdge.

While you’re here, be sure to subscribe to my YouTube channel for fun flight sim adventures.

When I’m not flying the virtual skies, I’m the sci-fi author of the Hayden’s World series. If you love exploration and adventure, be sure to check it out.